Motoring slowly along a superstore B road on the outskirts of a one-time cattle town called Newton Abbot, I see an elderly priest walking a narrow pavement. He’s stencilish, almost jagged, like a Richard Hambleton Shadowman painting. Clad in black, wearing gold-framed spectacles, carrying a black brass-clasped attaché case. His denomination was unclear, but his gait suggested a man chafing.

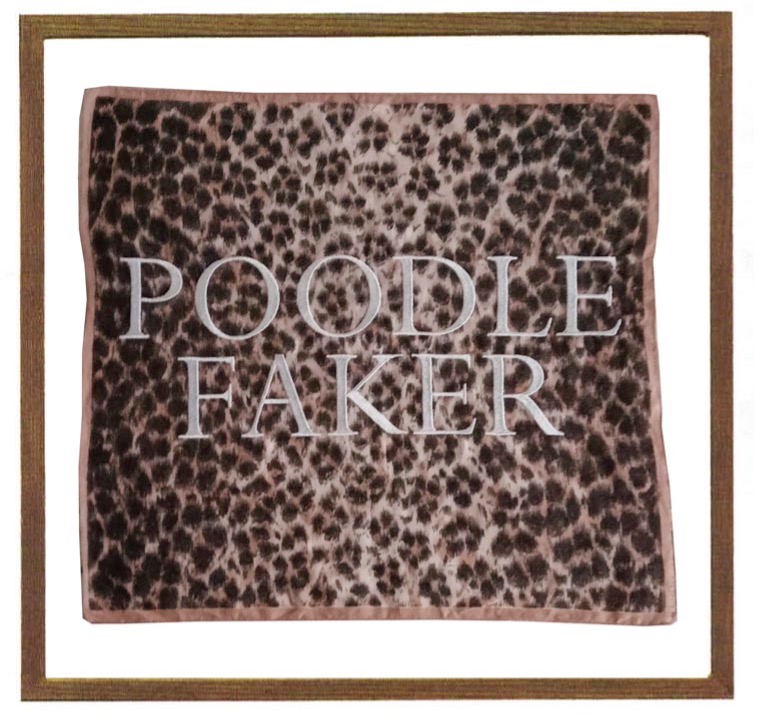

I’m on my way to see the Poodle Faker.

Within half a mile I spot another holy man of the cloth, this one younger than the first and he’s toting a contemporary rucksack clasping the straps like a hardened bell ringer. It’s a beautiful crisp February morning and I’m sparking well at one with the double expresso and faint diesel tang of the motor. Thoughts flit, like gold edged, cigarette paper thin bible pages. Could this be a media priest, a regular on Radio 2 like the one-time upbeat Rev Richard Coles? I drive cautiously after this sighting, not sure if this situation (seeing two priests) falls into any category of superstition like saluting magpies, cutting my nails on Fridays or Sundays or placing a hat on the bed. I never did ask my mother why anyone would want my nails and I still believe thunder and lightning are angels moving their furniture. The motor laps up the road as I imagine the media priest sharing something of his possible adventures with his tuned-in radio flock:

As I ambled through the village, I was aware of the number plates on the passing vehicles with the numeral 3 in them. Interestingly there were more number plates with the numeral 3, representing the Holy Trinity, than there were number plates with the number 6, representing the enemy. This is good news and I feel bodes well for the collection today…

I create these distractions to comfort myself. I remember in the Stephen Poliakoff film Shooting the Past the actor Timothy Spall uttering the phrase but I know how life works. Those words resonated with me because I don’t: I just don’t do life very well. I relate to individuals such as the Poodle Faker and I sincerely believe it is my duty to record their obtuse activity like a British Studs Terkel. To document and find great personal comfort in their rich contribution to the esoteric, to a disappearing social history. No doubt within the clip-boarded parameters of Toyota Prius driving support workers he could be pigeon-holed, given a mental health title in that curious critical jargon of the numbingly well-pensioned dull.

I pull into the narrow weed-tufted driveway, behind a series 244 Volvo with faded burgundy paintwork, that is parked close to a leaning potting shed. Almost immediately Clive the Poodle Faker appears. He stands theatrically in the arched verandaed 1920s doorway with the hyper-intense air of a potential violent suicide. I could picture him falling backwards from the parapet of a French-engineered suspension bridge, arms outstretched like a John Lewis Jesus. A tired grey Bovey Tracy bungalow shows blistering render and rusty drainpipes, the type of dwelling to draw the attention of unscrupulous doorstep merchants driving tired Transit vans advertising on magnetic signs their Acme business pay-as-you-go number. The type of transient trader who when paid in cash smells the notes for clues of concealment. The bungalow suggests pelmets, small Wade figurines and the scratch marks of departed cats.

It later transpired the bungalow had originally belonged to Clive’s Auntie Pamela, a compulsive knitter, spinster and volunteer.

I have never known an easy Clive: every Clive I’ve met was trammelled and had bony hands. Particular names appear to attract certain qualities. I cite Vivienne and Wendy as strong examples. Clive reminded me of a boy I went to school with called Paul Pendle. Paul had been born old. I saw him many years later, when he was in his forties, wearing almost Farrow & Ball Teresa’s Green, council overalls and tending a bowling green near the sea front in Paignton, Devon. It looked like he had arrived. He was perfectly in context. I remember he dithered as a youth and now he emanated the air of a gracefully moving bowling-green expert: placing pellets, stepping softly.

I am welcomed and as we go through to the lounge, I notice Clive is shod with highly polished brown brogues, wearing well-pressed tweed trousers and a duck-egg blue sleeveless cardigan. Clive is also in context, and he does not dither. He points to the rotary dial telephone saying If my thoughts were hand cream I would ring more often. As I sit down in a green velvet 1950s Zanuso armchair I ask him what he means by the comment. Oh, it’s just a saying I collected from one of my Barbaras.

Clive always refers to his women friends as Barbaras and of course only with their complicity for Clive is a gentleman. Apparently, his latest Barbara possessed a remnant of Isadora Duncan’s fateful scarf and drove an original red Fiat 500. He told me he had met her at the autumn fair held in the local community centre. Shehad been selling copies of her self-published romantic novella entitled The Amorous Butcher’s Love Slate: a torrid tale of passion amongst sawdust, dead beasts and the cold metal of mincing machines.

Clive could be regarded as a man who spent too much time in the society of women, engaging in such activities as tea dances and séances – events that actually occur more often than one would think in this day and age.

While it all sounds flippantly amusing, let us not lose sight of Clive the Poodle Faker poised on the parapet of the suspension bridge. Oh yes, there exists a very real feyness, a loneliness within this man and within this bungalow of someone else’s life. I notice that when Clive speaks, he moves one of his hands, fingers pointing vertically, in an up and down fluttering motion, like an absolution. I have seen this mannerism before: the American filmmaker David Lynch has the very same affectation.

I ask Clive why he is attracted to older women. He tells me that he felt he’d always left things too late and being enfolded in the company of his Barbaras gives him a great sense of comfort and belonging. He flicks the tassels of a brilliantly coloured shade on a turned-wood stand and points at a cream and black Cadillac-fronted Bakelite radio and then elaborates:

When I was a schoolboy, I had a friend whose mother was the mistress of a successful bookmaker. I would often go around to their flat – it was above an antique shop. She had flame-red hair and smoked Embassy cigarettes that she theatrically lit with a heavy Dunhill lighter. I always thought she was like a Hollywood movie star. There was glamour about her, but I didn’t know what it was: the lipstick stained cigarette ends in the Johnny Walker ashtray, the perfume, and the high heels. She always listened to Radio Four. I’d never heard it before or the classical music that would waft around gentle conversation and inquiry. She wore small pearl earrings and poodle brooches with diamanté eyes. I can never remember eating anything when I visited. We listened to plays on the radio, where I heard things like Fix yourself a drink while I get ready. There was always a promise of something – suitcases with travel tags, French windows, car doors slamming, tinkling glasses and RP endearments. This woman opened possibilities that I could not name at the time, but they stayed with me.

An image, a talisman, a comfort.